The Deload helps you be a smarter growth investor. If you haven’t subscribed, join over 1,300 independent and unconventional thinkers:

If you held an equal-weighted portfolio of the “Nifty Six,” you’d be up 49% YTD vs the S&P 500 up 9% and the Nasdaq up 18%.

No, the Nifty Six aren’t a group of nascent unprofitable tech or biotech companies. They’re some of the highest-quality companies in the world: Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, and Meta.

The biggest theme of markets this year has been the flight to quality, particularly to megacap tech. The Nifty Six have contributed more than half of the overall index performance to year-to-date.

Strong outperformance or underperformance of any stock or stock grouping always begs the mean reversion question: Have we gone too far?

Nifty Six vs Nifty Fifty

In the 1970s, the US economy dealt with a long period of persistent inflation and slow economic growth. Many have highlighted parallels to that period and today. Whether or not it’s a perfect comparison, one parallel that does seem apt is the emergence of the Nifty Fifty.

The Nifty Fifty was a group of the high-quality stocks of the day in the 60s and 70s. The group included quality giants that persist today including Procter & Gamble, Coca Cola, Pepsi, McDonald’s, IBM, Disney, and American Express. It also included sewing pattern company Simplicity Patterns, camera tech leaders Polaroid and Eastman Kodak, and CPG company Cheesbrough Ponds (which was acquired by Unilever, but the name is just fun).

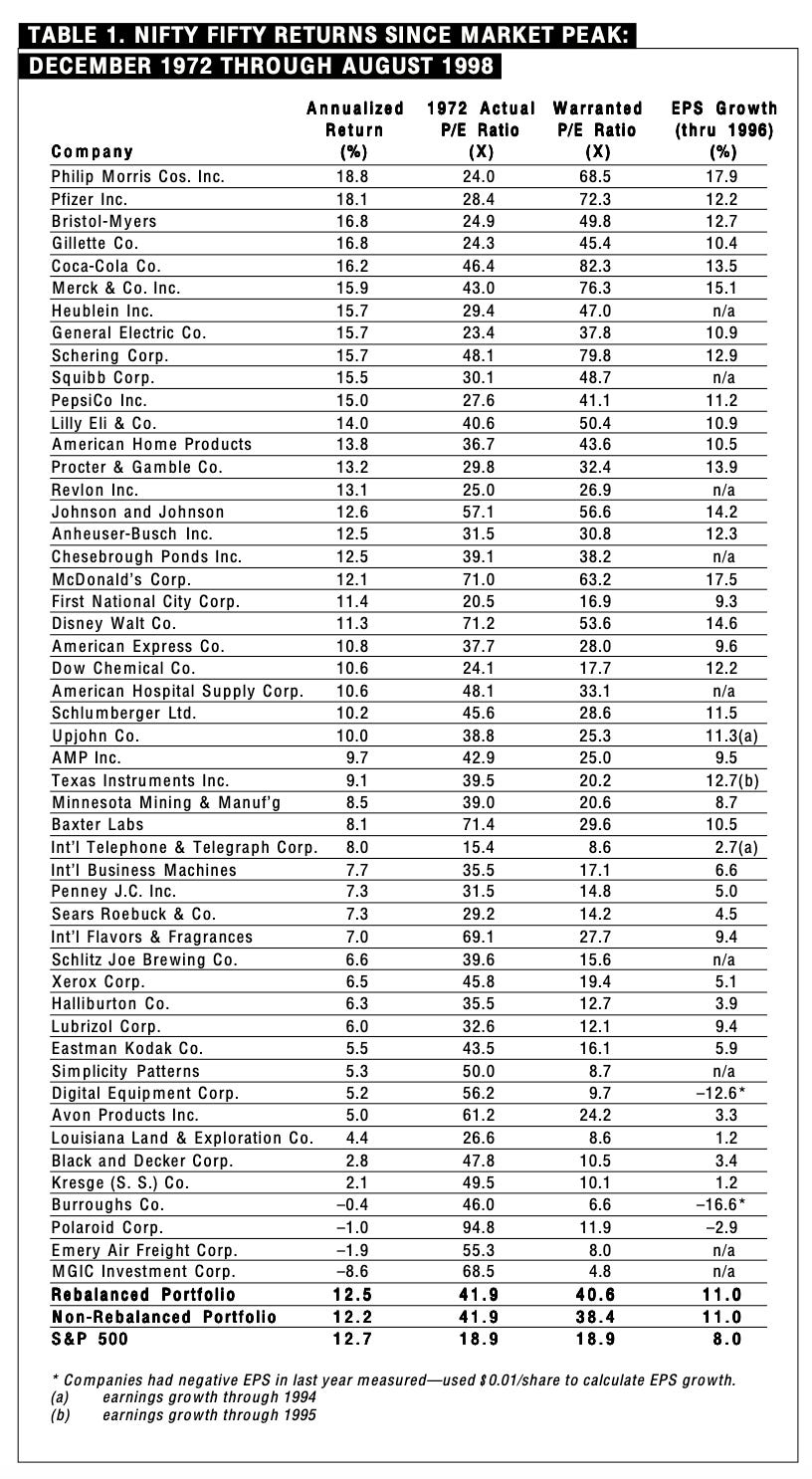

The reason the Nifty Fifty exists in investment lore isn’t because of the stocks in the group, it’s because those stocks were the bubble stocks of the day. In 1972 when the Nifty Fifty were peaking, the group traded at an average P/E of 42x and median of 40x. Polaroid traded at 95x earnings, the highest of the group.

The market doesn’t get them all right.

By comparison, the Nifty Six trades at an average trailing P/E of 41x and median of 25x. The group’s average forward P/E is 32x and 2023 cash flow yield is 3.6%. Amazon is the most expensive stock by forward P/E at 59x. Nvidia only trades at 49x.

So, back to our question: Have we gone too far?

Maybe.

The bear case on the Nifty Six is that the parallels to the 1970s play out the same as they did for the Nifty Fifty. After the Nifty Fifty roared to peak valuations in the early 70s in perhaps a similar flight to quality as we see today, the US economy entered recession at the end of 1973. The stock market, as it almost always does, bottomed in the middle of the recession in 1974.

From 1972 to 1974, the S&P 500 lost 36% of its value. The Nifty Fifty lost 50%.

If the US enters recession, which is what “everyone” seems to expect, although the markets don’t seem to be pricing it, one could make a case for the Nifty Six to correct more than the market given their relative dominance over the past several months.

Few stocks are spared in recessions. To the extent indices sell off, the Nifty Six will as well, but I’m not sure that we should expect investors to overweight selling individual Nifty Six holdings vs other stocks. The Nifty Six is a concentrated group of high-quality global companies built on unique intangibles, which sets the group up to weather a storm better than most. It’s hard to imagine mega cap tech not being relevant for decades future just like P&G, Coca Cola, and McDonald’s of the Nifty Fifty.

That’s the bull case — to look at the long term.

NYU Stocks for the Long Run Prof Jeremy Siegel did an analysis on what P/E each of the Nifty Fifty stocks could have traded at in 1972 and still generated market returns if investors held them through 1998. Several of the Nifty Fifty stocks could have traded at P/Es even higher than what they traded at in the 70s including Coke, Gilette (P&G), Phillip Morris, Pepsi, and Pfizer. The universal key was persistently robust earnings growth.

I think superior returns in the medium term are more likely to be found outside of the Nifty Six than concentrating in the megacaps, but Siegel’s work shows the case to keep owning them. To the extent an investor can look through whatever macro environment comes over the next year or so, he probably does fine holding the Nifty Six as it seems more likely those stocks deliver on persistently strong earnings growth over the long run.

The Not Everything Bubble

An idea I’ve been kicking around since the beginning of the year was that the next bubble would be a quality bubble, and it could happen sooner than later. A Fed cutting cycle through a recessionary correction could be the catalyst.

I call it the Not Everything Bubble, which stands in contrast to the Everything Bubble of 2021. It wouldn’t make sense for speculative mania to return to random NFT projects, dog coins, SPACs, meme stonks, or unprofitable flying car companies. Those assets just burned everyone. Most of the time we don’t burn our hands twice on a stove in short succession.

The striking characteristic of the Not Everything Bubble will be its concentration in a few quality assets rather than the breadth of the Everything Bubble. There is only so much quality or perceived quality, and we mostly know it when we see it, e.g. the Nifty Six. The Not Everything Bubble will overweight quality to an extreme, funneling money into a few assets to drive wild prices.

In stocks, the money funnel will focus on high-quality businesses driving strong cash flow generation (or close to it). The same mentality we’re seeing with the Nifty Six could extend to midcap names with similar quality indications and higher-growth potential. Former speculative darlings with no hope of profit have no hope of getting a sustained bid.

In venture, money won’t rain on every idea that shows up. Instead, companies that compete in the biggest market opportunities with more apparent profit potential will accrue as much capital as they want. Market picking will be the dominant winning strategy, at least for markups. We may be seeing the early indications of this with venture investor focus on AI now.

In crypto, Bitcoin will reign supreme via its inherent scarceness. Dog coins and NFTs will be ignored. As a byproduct, Ethereum will not get the same bid as Bitcoin. Balaji will probably be right again, at least directionally.

Whereas the Everything Bubble arguably created more competition via seemingly unlimited capital available to any crazy idea, the Not Everything Bubble will concentrate capital amongst a few. Alfred Lin of Sequoia once said, “Capital accrues to the winners.” The inverse statement is also valuable. Those who accrue capital are more likely to win.

That’s the net result of the Not Everything Bubble — an increase in winner-take-all outcomes. Ironically, winners taking all might make paying crazy prices end up being not so crazy…if you can hold on to them for the long run.

Disclaimer: My views here do not constitute investment advice. They are for educational purposes only. My firm, Deepwater Asset Management, may hold positions in securities I write about. See our full disclaimer.