The Four Investor Archetypes

Value vs Growth is Dead

Investing philosophies are traditionally separated into value and growth. Value investors buy beaten-down stocks that appear to be cheap. Growth investors buy stocks with high growth potential but often appear expensive.

There’s a more useful way to consider investment philosophies across two axes: concentrated vs diverse and cash flow conscious vs cash flow unconscious.

These four investor archetypes are the more accurate way to describe investor strategies whether the underlying be stocks, startups, crypto, or something else.

Concentrators

The concentrator prototype is Warren Buffett, but to call this the Buffett investor would too closely align with the traditional definition of value.

Smart investors have always challenged that value and growth need to be separate. Growth stocks can be cheap if the future cash flows they ultimately generate aren’t reflected in the stock price. Value stocks can be value traps that fail to generate cash flows assumed in the stock price.

In tech and innovation investing, value is particularly hard to determine because so much of the value these companies will generate is so far in the future. That doesn’t mean investors shouldn’t try. I think the most effective way to invest in tech is to determine what’s priced into the stock defined by the level of growth required to generate cash flows to justify the current price. Given this necessary growth, what are the company’s chances of greatly exceeding that outcome? How does this compare to historical growth rates of comparable and even great tech companies?

Concentrator is doubly relevant as a descriptor for this investor because it not only describes the relative number of positions but also the understanding of those positions. Having a strong view on how a company can generate future cash flows, along with a strong margin of safety, gives the concentrator comfort in only owning a small number of positions. This could be single digits, or it could be a few dozen at varying weights.

Any Buffett disciple obviously fits in this category, but some high-quality traditional venture investors are concentrators, too. Portfolios are relatively limited, and those who reserve capital to follow on to the biggest winners become quite concentrated over time.

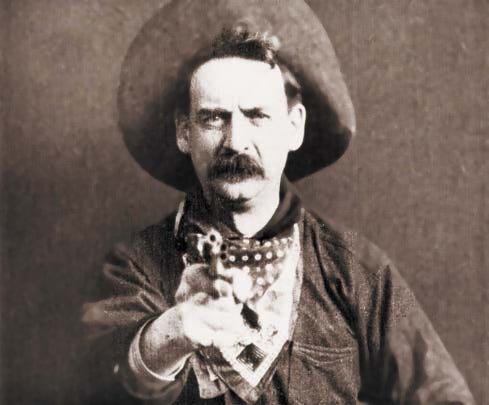

Gunslingers

A lot of gunslingers think they’re concentrators, but they’re fooling themselves. Most commonly, they’ve convinced themselves that something other than future cash flows is the most important determinant of future value. Many public market investors in disruption fit here. So do many venture capitalists and most crypto investors.

If you aren’t considering future cash flows as the most important thing, you’re speculating. When you speculate, you’re gunslinging.

If you’re gunslinging, it’s best to know it. Most meme stock and meme coin buyers know they’re playing in the casino, not investing. It doesn’t mean they’ll win, but it means they have a better chance of not losing than those who don’t understand the game.

That doesn’t mean gunslinging is a bad strategy. There are many great gunslingers that understand technology and human psychology well enough to invest in things early and sell when the rest of the world gets excited. The best gunslingers have an acute understanding of supply and demand because that is all that determines the price of assets when cash flows are ignored or non-existent.

Gunslingers that hit on the right idea often enjoy returns far more dynamic than any of the other core investing archetypes.

Explorer

Where Buffett is the prototypical concentrator, Peter Lynch is the greatest explorer. His aptly named Magellan fund often held more than 1,000 stocks in his tenure. That’s not a concentrated strategy. Despite the large number of holdings in Lynch’s fund, he was deliberate in what he added. He understood the ability of his stocks to generate future earnings and cash flows.

While there have been many to successfully imitate Buffett and Munger’s principles of concentration, few have followed in Lynch’s footsteps.

The thing investors misunderstand about the explorer category is the necessity for dynamic upside in the many positions in the portfolio. It’s not that Lynch was able to choose lots of stocks that did a little better than average, he was great at finding ten baggers — stocks that increased 10x or more over his holding period. Lynch invested in more than 100 ten-baggers in his career. Over thousands of positions, those dynamic returners are what allowed for Lynch’s exceptional performance.

Investors that try to use the explorer strategy but don’t optimize for ten baggers only end up indexing. The only way to find enough ten baggers to make the strategy work is to look where others aren’t.

Indexer

The indexer strategy is the simplest to explain. You just own the market. You buy the SPY or the QQQ and accept what the market gives you.

How Does Each Strategy Win?

The concentrator wins by not losing a lot when wrong and making a lot when right. The latter point means scaling into the right investments is important.

The explorer wins by having a few major outperformers with dynamic upside.

The gunslinger wins sometimes by understanding supply and demand but more often by getting lucky.

The indexer doesn’t win or lose by definition. They get whatever the market gives them. Proponents of passive investing argue that earning market returns is winning. Proponents of active investing say it's losing because index investors readily accept badly priced assets with the good.

Uncomfortable Profit

Every investor must heed the four investor types to hold himself to the strategy he thinks he’s implementing. Beyond this obvious and important lesson, there’s a lesson for the investment business builder.

A lot has been written on Tiger’s private equity strategy around high velocity investing. We could debate whether the strategy is an explorer or index strategy, but the bigger point is that Tiger did something in venture that the rest of the industry hadn’t figured out.

Venture is full of concentrators and gunslingers. By simply using an approach that wasn’t being used, Tiger’s already won.

Contrast Tiger’s strategy, which was a unique philosophy in the venture industry, to Softbank’s Vision Fund. The Vision Fund was the same philosophy as the rest of the industry, just with more money. The unfailing rule in all investing is that larger size makes it harder to use the same strategies that work with smaller size. For the Vision Fund, size didn’t give Softbank a unique advantage, it just made them go harder into gunslinger mode.

Crypto is set up somewhat similarly to venture — lots of gunslingers and indexers. Not many that apply cash flow sensitivity, largely because it can’t be done. That’s why I’ve been following the NFT space given the dividend stream those assets often come with. It’s still early, but someone will build a great concentrator or explorer fund, probably the latter, around NFTs.

In investing and business building, and in investment business building, doing the thing others aren’t is always the path to extraordinary returns.