Survey Says We’re in an AI Bubble Already

And the virtue of staying with good ideas

The Deload explores my curiosities and experiments across AI, finance, and philosophy. If you haven’t subscribed, join nearly 2,000 readers:

Disclaimer. The Deload is a collection of my personal thoughts and ideas. My views here do not constitute investment advice. Content on the site is for educational purposes. The site does not represent the views of Deepwater Asset Management. I may reference companies in which Deepwater has an investment. See Deepwater’s full disclosures here.

Additionally, any Intelligent Alpha strategies referred to in writings on The Deload represent strategies tracked as indexes or private test portfolios that are not investable in either case. References to these strategies is for educational purposes as I explore how AI acts as an investor.

The Market Thinks We’re in an AI Bubble Already

And we’re going higher.

At least that’s the consensus from a 1,300 person survey I ran on X this week. Almost 46% of respondents said we’re already in an AI bubble and will go higher. For what it’s worth, I agree with the 34% who think we’re not in a bubble, but we’ll get one.

That 90% of respondents think we’re either in an AI bubble already or we’re going to get one makes me wonder: Can we really get an AI bubble when it seems like everyone expects it?

We Always See the Bubble Coming

Famed Yale economist Robert Shiller wrote Irrational Exuberance at the peak of the Internet bubble in 2000 suggesting that markets were…too exuberant. His timing was impeccable. Less well known of Shiller is a study he did during the 90s bull market where he assessed changes in investor sentiment over time.

The study analyzed a series of surveys asking whether investors thought asset prices were too high/low/etc, whether they thought markets would go up or down in the future, and whether they felt others around them were showing “a great deal of excitement and optimism about stock markets.” Shiller created an index from the responses to describe whether investors thought the market was in a bubble or not. The index suggested that throughout the mid-to-late 90s, investors floated between periods of heightened bubble awareness and periods with more muted expectations.

90s investor sentiment trended with the market. As markets boomed, concerns about the bubble increased, and those concerns receded with the market. Price drives sentiment.

And that brings us to the current state of markets. We’ve largely been up and to the right, save for a few 10%-ish corrections, since the bear market bottom in 2022, which also coincided with the launch of ChatGPT. Price seems to be driving the large majority to say we’re in a period of great optimism, but the Shiller data tells me that won’t stop us from bubbling even more. Shiller’s index says the market had peaky bubble feelings in 1993 (arguably the start of the Internet boom), 1996, and 1998, and we all know the ultimate peak wasn’t until 2000.

Maybe the better question is can you have a bubble when no one expects it? I don’t think so. Bubbles are driven by psychology, not secrecy. Optimism and fomo are contagious, not subtle. The AI bubble will stare us right in the face as it's happening, if it’s not already here.

Where are We in the AI Bubble?

Clearly nowhere near the insanity of the Internet era:

NVDA trades at 40x forward earnings. Cisco peaked at over 100x in the Dotcom bubble.

The Nasdaq 100 trades at 26x forward earnings. The Nasdaq 100 traded near 100x in the Dotcom bubble.

An Intelligent Alpha index of AI companies, the AI Average, trades at 53x earnings. The Nasdaq peaked around 200x in the Dotcom bubble.

There are also hints from the data in my survey compared to that of Shiller’s.

Shiller’s survey measured how many respondents believed that markets were too expensive and would keep going up and also those who thought markets would soon crash. I tried to replicate similar responses in my survey responses, e.g. we’re in a bubble and going higher, and we’re in a bubble and about to crash.

The strong sentiment from my survey is that we’re going higher vs ready to crash. This seems to correlate to late 1995 or late 1996 in Shiller’s survey where respondents generally thought markets would keep going up and had minimal concern for a crash.

The adage that bears sound smart and bulls make money applies here. There were smart sounding bears in 1995, 1996, 1997, and later, and they missed one of the biggest bull markets ever. The consensus of the market through the 90s showed that it understood what was happening better than the “smart” bears — a bubble was forming, and the market was going to keep going higher.

The Internet bears were right about being in a bubble, but timing and positioning matters in markets. A lot of “smart” bears went out of business trying to short the obvious, and there were plenty of smart investors who did get out of the bursting bubble with incredible profits. Those who make money in markets are the smart ones, not the bears that lamented the obvious all the way up with nothing but words to show for it.

Disclaimer: My views here do not constitute investment advice. They are for educational purposes only. My firm, Deepwater Asset Management, may hold positions in securities I write about. See our full disclaimer.

Intelligent Alpha: Faith in a Good Idea

Every good idea survives in part through faith. An idea that is plainly obvious doesn’t need faith. Such an obvious idea can’t be a good one because a good idea must come with a meaningful reward. The reward of obvious ideas has already been captured by those who figured the idea out first.

The past month has come with frustrating returns that have tested my faith in Intelligent Alpha, the AI-powered investment platform I’ve been building over the past year. The good news is that more than 70% of the strategies I track are ahead of benchmarks since inception, and 60% are ahead of benchmarks YTD.

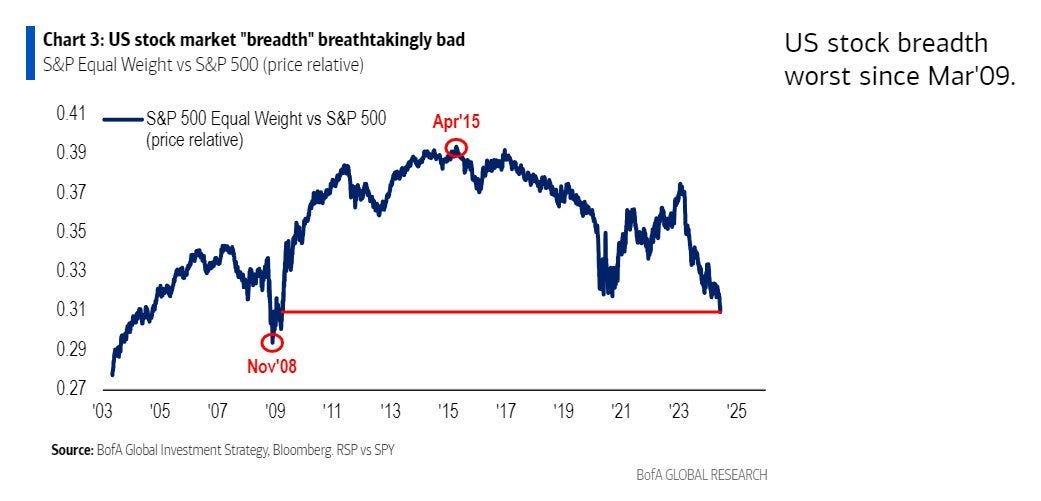

But only about 40% of the strategies exceeded benchmark performance over the past month. Many of the underperforming strategies are benchmarked against US Large Cap comps like the S&P 500 where market breadth has been awful.

NVDA is up over 35% in the last month, contributing a little under 2.5% of the performance of the S&P 500 (+3.9%). If you’re underweight NVDA, and many IA strategies are, it’s mathematically hard to keep up. For the year, I believe NVDA has contributed something like 7% points to the performance of the S&P 500 (+14.5%), which makes me feel a bit better about IA’s strategies generally holding in despite the lack of breadth.

Headwinds can become tailwinds. If NVDA ever slows down, perhaps a dangerous thing to assume given where we are in the AI boom, Intelligent Alpha’s underperforming strategies could look a lot better.

To put more data on the breadth issue, the largest decile of companies by market cap in the S&P 500 have performed the best this year, and the bottom decline has performed worst. This performance dynamic obviously helps cap-weighted indexes.

Intelligent Alpha strategies aren’t cap-weighted, they’re AI weighted. Since the beginning, IA strategies have generally been somewhat underweight bigger companies and overweight smaller ones. For example, the IA Large Core strategy, which I comp against the S&P 500, has more than 60% of its portfolio by weight in stocks under $100 billion market cap. The S&P 500 has only 28% of its weight in those companies. That same IA strategy also has 23% of its weighting in companies in the bottom 40% of S&P market cap vs under 7% for the S&P itself.

Short term performance measurements are always fraught time periods to analyze investment strategies. Shorter durations highlight the randomness and noise that is smoothed over longer time periods. The goal of Intelligent Alpha, as it should be with all good investment strategies, is to add excess return in the long run.

Despite the tough month for Intelligent Alpha, I still have faith that AI is the future of the investment management world because it corrects the major flaws of our current options in passive and active management.

Passive Investing

The flaws of passive investing are:

Fundamental misallocation.

A lack of qualitative intelligence.

The impossibility of alpha.

Misallocation of Indexes

Indexing may be smart in a world where most active managers can’t beat them, but indexes aren’t smart.

Traditional indexes misallocate capital because most use cap weighting. In a cap-weighted index, the largest stocks get the largest weight (e.g. AAPL in the S&P 500), and the smallest stocks get the smallest weighting, but market cap isn’t an accurate predictor of future investment performance. To the contrary. Large market cap is often a signal of higher valuation, and that may point to a headwind to future performance.

Rob Arnott built the Fundamental Index at Research Affiliates on the notion that indexes inherently misallocate capital. Fundamental Indexes use metrics like sales, cash flow, and book value to establish relative weights in the index rather than market cap. Arnott argues this reflects economic value rather than market value, but the more important point is that Fundamental Indexes decouple weighting from market cap to avoid the reality of larger stocks tending to get overpriced and smaller stocks underpriced in an index.

Smart beta is the way indexes try to improve investment decisions, but smart beta is still built on numbers. It doesn’t add any qualitative understanding of the companies in the index, which is the better way to predict the future.

Qualitative Intelligence

Qualitative intelligence about a business is the core advantage of the active manager. The active manager’s understanding of inherent advantages and disadvantages of a business helps him to predict a future for that business that cannot be predicted with historical data alone.

Indexes can never reflect qualitative intelligence because qualitative intelligence is not quantifiable. The best we can do is smart beta or quantitative investing, but the managers of those strategies will admit that their indexes and machines don’t know the difference between AAPL and APO. Nor do they care. Rules based systems, no matter how complex, do not understand the actual businesses they invest in, and that denies them the greatest absolute source of alpha.

Impossible Alpha

If you invest in a major index like the S&P 500 or Russell 2000, you can’t generate alpha. That’s the point of passive investing. You accept the market return for the comfort of knowing you won’t do worse than the average over time.

Smart beta and quantitative factors can help create relative advantages vs indexes, but they often come with periods of painful underperformance that seem a necessary quality of factor-based risk premia. If some factor outperformed the market all the time, it would get crowded out by the market. Factors are a strong tool for investors with an appropriately long-term oriented mindset, but straight indexes are probably better for most.

A dynamic approach that qualitatively understands businesses and dynamically moves to the best opportunities is the only way to achieve persistent alpha; however, that road is littered with many who tried and failed. Markets are stubborn. Humans are impatient. Creating persistent alpha is hard. That brings us to the failures of active management.

Active Investing

The flaws of active management are:

Inconsistent returns.

Mistakes driven by emotion.

Durability of managers.

Inconsistent Returns

While you can’t generate alpha through passive investing, that doesn’t mean the returns are merely average. Passive returns are the average of all participants, but Patrick Geddes (founder of BlackRock’s Aperio) argues that passive returns aren’t an average outcome in the long run. Passive returns are actually well above average because indexes beat 90% of active managers over the long run.

I’ll reference the SPIVA report once again:

A human manager has a decent shot at beating the benchmark in any given year, but as the years compound, fewer and fewer managers are up to the task. Geddes’ insight is that by accepting passive returns, you guarantee a very good return vs most active alternatives in the market. You’re just giving up the chance for stellar returns that are consistently achieved by few active managers.

Emotional Mistakes

A core reason for inconsistent active returns is that humans make emotional mistakes. We capitulate in pain often when we should do the exact opposite. We pay attention to the short term, like monthly returns, even though our objectives are long term. We fixate on hockey stick stock charts, making us fearful of what might come next without any consideration for fundamental realities.

The greatest investors are great because they’ve figured out how to manage emotional pain. So many of Buffett’s famous quotes are about emotion, not investing:

“Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.”

“The difference between successful people and really successful people is that really successful people say no to almost everything.”

“The most important thing to do if you find yourself in a hole is to stop digging.”

A lot of investors like to think they invest long term, but they get hit for a year or two, or they miss an NVDA, and they go on tilt. It’s actually insane that Buffett, for 60 years, has managed to avoid the temptation of stocks that appear to present good 1-3 year prospects in favor of the far fewer opportunities that appear to offer good multi-decade prospects. Yes, Buffett has a lot of leeway given his track record, something many managers don’t have. He’s earned it over time.

Durability of Managers

Even if you find a great manager, the manager is still human, and you’ll have to contend with his durability. The manager might make so much money that his style changes and performance suffers. The manager might similarly get distracted by divorces, boats, and politics. Even if the manager avoids all of the temptations of life, and truly loves investing with plans to do it his whole life, he eventually either loses his faculties or leaves our world. Such is the harsh reality of nature.

AI-Powered Investing

AI-powered investing fixes all of the disadvantages of passive and active management:

Better allocation. AI-weighted portfolios break the flaw of cap-weighted indexing. To the extent AI-powered portfolios weights are well-reasoned both quantitatively and qualitatively, they should better reflect the future prospects of those companies compared to indexes, smart beta, or quant investing. That should lead to better long-term results, although as we’re seeing now, it doesn’t mean AI-powered portfolios will win every single week or month.

Qualitatively intelligent. AI, unlike indexes or quantitative models, can understand the qualitative realities of a company, which allows for better predictions of future performance. Quantitative value advocates may say companies that trade at lower prices should outperform those that trade at higher prices over time, I would counter that companies with high quality, durable businesses trading at reasonable prices relative to growth should perform even better. You can only find the latter company if you understand the business itself, not just the historical numbers it’s generated.

Inconsistent Returns. AI-powered portfolios have the chance to generate more consistent returns than human managers because they don’t suffer from chasing near-term trends, style creep, the trappings of wealth, or the many other reasons that most active managers fail to beat benchmarks over long periods, especially emotional mistakes.

Emotional Mistakes. AI doesn’t feel the emotional stress of markets — the desire to chase when you’re underperforming, the desire to doubt stocks flying but with strong fundamentals, the desire to give into pain. By avoiding emotional pull, AI eliminates the biggest source of inconsistent returns from active management.

Durability. AI doesn’t get distracted by wealth, illness, or death. It’s eternally durable. A well-trained model with an enduring philosophy for allocating capital to great companies can do it as long as the AI lives on a server somewhere.

The point of all of these advantages is to generate persistent alpha. Indexes can’t do it, and most humans don’t. The goal for Intelligent Alpha is to shape it into the manager that lives in the top decile over time. The painful valleys are where learning happens. Learnings bring new insights. New insights drive improvements. Constant improvements support long-term results. That’s investing. That’s life.

The future of investing is still intelligent.