Buffett ❤️ Apple: Case Study

A Lesson in Investment Payback

The Deload is a weekly-ish newsletter that explores uncomfortable and non-consensus ideas about growth investing. If you haven’t subscribed, join almost 1,100 independent and unconventional investors and thinkers:

Buffett x Apple: Payback

Is it the bottom yet?

No one knows. We all know no one knows, but it’s easy to get sucked into the bottom-calling game.

We all also know that making money by calling a bottom isn’t the way to generate great investment returns. Great returns come from consistently buying assets for what turns out to be cheap prices.

Instead of trying to call the bottom, we should spend more time looking for assets that will turn out to be cheap in hindsight.

That’s what Warren Buffett did with Apple, and there’s a major lesson from Buffett’s Apple buy worth remembering today.

A Brief History of Buffett + Apple

Buffett started buying AAPL in mid-2016 when the stock was more than 25% off its highs for two reasons.

First, the company was going through a disappointing iPhone 6S upgrade cycle. “S” upgrade cycles were phones that looked exactly the same as the prior version but had better processors, camera features, etc. A spec upgrade vs a full device upgrade.

Second, and in part driven by the “S” cycle, sales in China stalled precipitously. Greater China revenues were down 26% y/y in Mar-16 and 33% in Jun-16.

The entire narrative shifted from Apple dominating the world as the most profitable and stable company to wondering if the iPhone trend was dead.

The challenging 2016 created a setup Buffett couldn’t avoid:

Apple had more than $150 billion in net cash on the balance sheet.

Apple was committed to buying back growing amounts of the stock.

Ex-cash, Apple’s free cash flow yield had been in the 10-11% range for the past several years. At the end of Apple’s FY16, it was over 12%.

With such strong free cash flow generation, Apple also fit a mental check common amongst many great investors (via Dakota Value Funds):

“Flipping that around, and using yield instead of multiples, we were shocked by how many of the greats, including Munger, Buffett and Glenn Greenberg, used the following equation to determine forever value:

Free cash flow yield + growth rate = return.

Generally, they were looking for companies where free cash flow yield + growth rate equaled 20% or more. In other words, they were looking for returns double the market average, which is exactly what all of them achieved over their long careers.”

Buffett bet that Apple’s business, while temporarily challenged, wasn’t going anywhere. He knew that people would be using iPhones for a long time even if they upgraded less frequently. And he knew that Apple would keep generating strong free cash flow that probably grew in the single-digit range even in that bear-case situation, getting him toward the 20% yield + growth hurdle.

He was right.

AAPL is up ~4x from where Buffett started buying it just six years ago.

What’s the Lesson?

A lot of things went right for Buffett with Apple. The iPhone turned out to be stronger than the market thought in 2016. Services has grown to be a significant part of the business. Market multiples have expanded for all big tech companies.

Here’s the most interesting thing: Between dividends and repurchases, Apple returned ~$490 billion since Buffett’s 2016 investment. The market cap when Buffett started buying Apple was $550 billion. So, the company almost literally returned its market cap in cash to shareholders over the past six years.

It’s hard to see a losing scenario when a company returns cash equivalent to its market cap in short order and sustains a strong ongoing business even after that return. That’s a can’t miss.

I don’t know if Buffett asked himself how quickly he could get paid back by investing in Apple, but it’s a question we all should consider more often. Especially growth investors.

Free Cash Flow Payback

Imagine you were going to buy a local laundromat today in cash. One of the first questions you’d ask is:

How long until I make my money back?

Yet, when we make an investment in a public company, few of us ask that simple question.

Why?

The reason we do ask it when buying the small business is several fold:

The investment is illiquid. We know we can’t just turn around and sell a laundromat, so we accept that the point of the investment is to cash flow, not see a number go up.

Multiples on small businesses are often much lower than multiples on public ones because, right or wrong, we assume the life of a small business is likely much shorter, meaning the terminal value is limited. We know we need to make money through the business in the nearer term, not rely on the hope of the long term.

These answers invert when we consider a public investment:

The investment is liquid and moves up or down every day. We can sell it whenever we want. We can make (or lose) a lot of money fast regardless of meaningful change to the underlying business performance.

Public companies often have proven an ability to serve customers on a national or international level with products or services likely to be valuable for a long time. Thus, public companies benefit from significantly longer assumed cash flow generation lifetimes than small businesses.

Both the liquidity and expected durability of public assets lull us into thinking more about relative multiples and whether earnings need to go up or down next year than the medium-to-long term prospects of the business.

Public investors are wrong not to ask the free cash flow payback question. If you’re really buying a business — and per Buffett, when you buy a stock you should think of it as buying a piece of a business — then you should care about getting paid back.

This is important: Getting paid back in a public investment doesn’t have to mean the company returns capital like Apple. It does mean the company has to eventually generate tFCF equivalent to the market cap at the time of purchase (or tFCF/share equivalent to purchase price).

Great growth companies can reinvest free cash flow at sustained high rates of return. Even though a growth company might not repatriate cash like Apple, it does reinvest it on the shareholders’ behalf. These are the ever desirable “compounders,” and we shouldn’t want such companies to return cash to us.

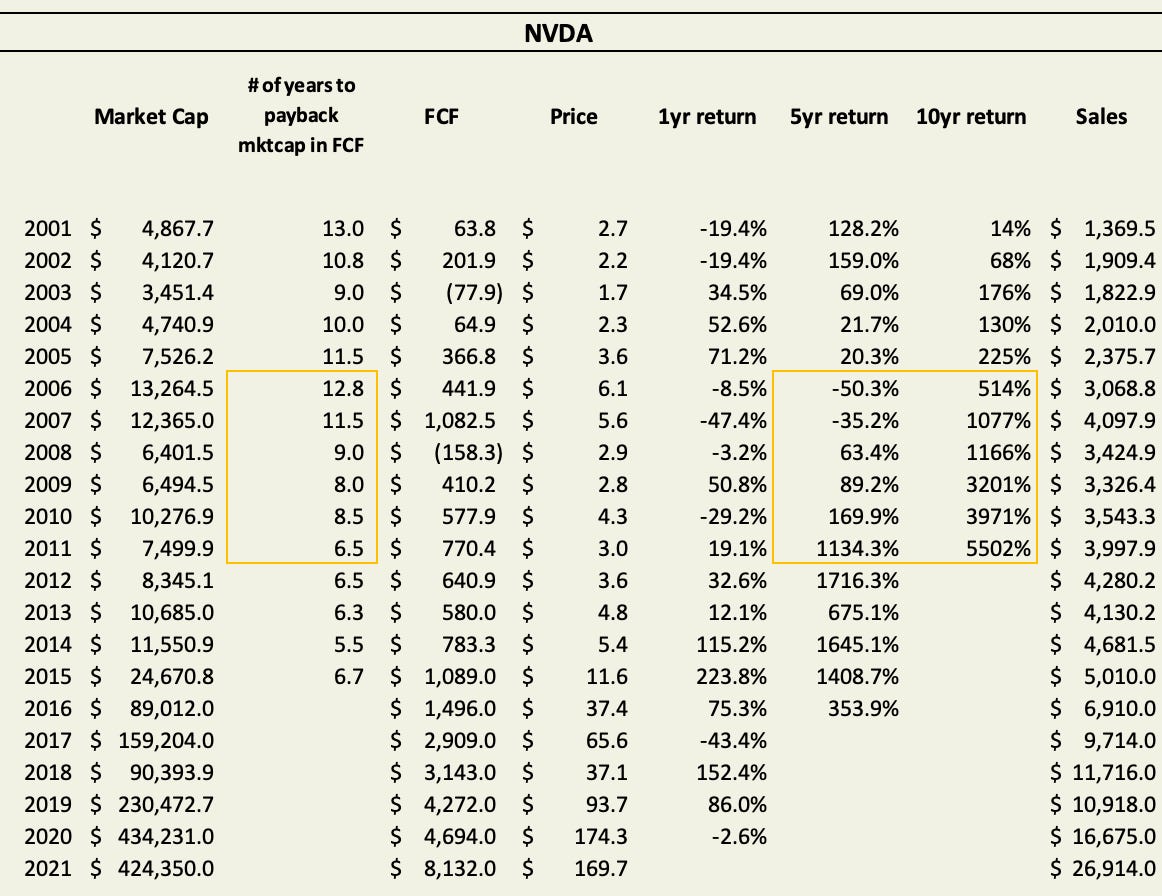

My colleague Will Thompson wrote a post describing a study he did about definitively great growth companies that generated FCF equivalent to market cap. Historically, growth companies that generate their market cap in FCF in 6-10 years have also generated great long-term stock returns.

Mathematically, this makes sense. A fast-growing company is going to return a greater and greater percentage of the original market cap in cash the further we go out in time. If a company generates, say, 50% of its base market cap from eight years ago in FCF and it gets a 20x FCF multiple, that’s a 10x. A 10x FCF multiple is a 5x.

And the faster they generate FCF equivalent to the prior market cap, the better the stock returns.

Sanity Check

tFCF payback isn’t a tool to establish the value a laundromat, nor is it a tool to value public equities. It’s a way to test the sanity of the investment.

Great growth investments should payback their market cap in tFCF in less than 10 years. Why should we want to invest in any business where we can’t even make our money back in a decade, nonetheless start generating a cash return?

A lot changes in a decade. If you don’t think there’s any way you can make your money back in tFCF in less than 10 years, it’s probably not going to be a great investment. The stock might modestly beat the market over the long term. It might go up near term with favorable earnings, but it won’t be Apple, and it won’t generate legendary Buffett-like returns.

Notes and Quotes

Tech Layoffs

Last week, we talked about how more tech companies should take the current environment to rightsize headcount. More companies joined the trend this week: Unity, AppLovin, GoDaddy, UIPath, and a dozen-plus more.

Over 60,000 tech workers have been laid off in the past year, mostly the last five months. And this chart doesn’t reflect the many venture-backed companies that haven’t and won’t make it.

It’s sad for the employees. It’s right for the long-term viability of the companies. It’s responsible for investors.

Great info. As an English major I take no umbrage because it is true to a point. However, the investment graveyard also has its share of bean counters. I'm a particular fan of Damodaran's book _ Narrative and Numbers_ you have to have a measure of both. The best opportunities often arise when the narrative has led too many to believe in near term risks like the S iphones or like Amazon's transition away from SunMicro in '03 when I got a little bit at 12 even though the risks in both cases were real the narrative and the general short term focus of most investors led to mispricing.

Ah yes, uncomfortable. Federighi and Srouji can't comfort retail investors, even though they explain in detail why Apple has a moat the size of Lake Huron.

Retail investors get nervous when bobble heads talk about rumors, or lack of a foldable phone, or their endless stream of correlations that have no predictive power at a time when the future is uncertain.

But I buried the lede, "increasing IB, increasing ARPU".