Benchmarking AI Stock Performance with the AI Average

Quantifying the AI sector's outperformance and valuation

The Deload explores my curiosities and experiments across AI, finance, and philosophy. If you haven’t subscribed, join nearly 1,500 readers:

Disclaimer. The Deload is a collection of my personal thoughts and ideas. My views here do not constitute investment advice. Content on the site is for educational purposes. The site does not represent the views of Deepwater Asset Management. I may reference companies in which Deepwater has an investment. See Deepwater’s full disclosures here.

A Brief History of Stock Indices

Did you know the S&P 500 is not passively managed?

The S&P is actively managed by a committee that makes 500 stock selections according to certain rules, not purely passive guidelines. As a former committee member states, “There are no rigid or absolute rules for the S&P 500; the Index Committee has some discretion in selecting stocks or responding to market events.”

The same committee selection process is true of the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) too. From the selection process of the DJIA: “While stock selection is not governed by quantitative rules, a stock typically is added only if the company has an excellent reputation, demonstrates sustained growth and is of interest to a large number of investors.”

When we try to beat the market, we compete against active benchmarks in which the managers trade rarely. Perhaps there’s something to Terry Smith’s “own good companies and do nothing” since that’s what the indices do.

I find stock indices fascinating. Not just because of the pseudo active management of the biggest ones but because of how they’ve evolved over time.

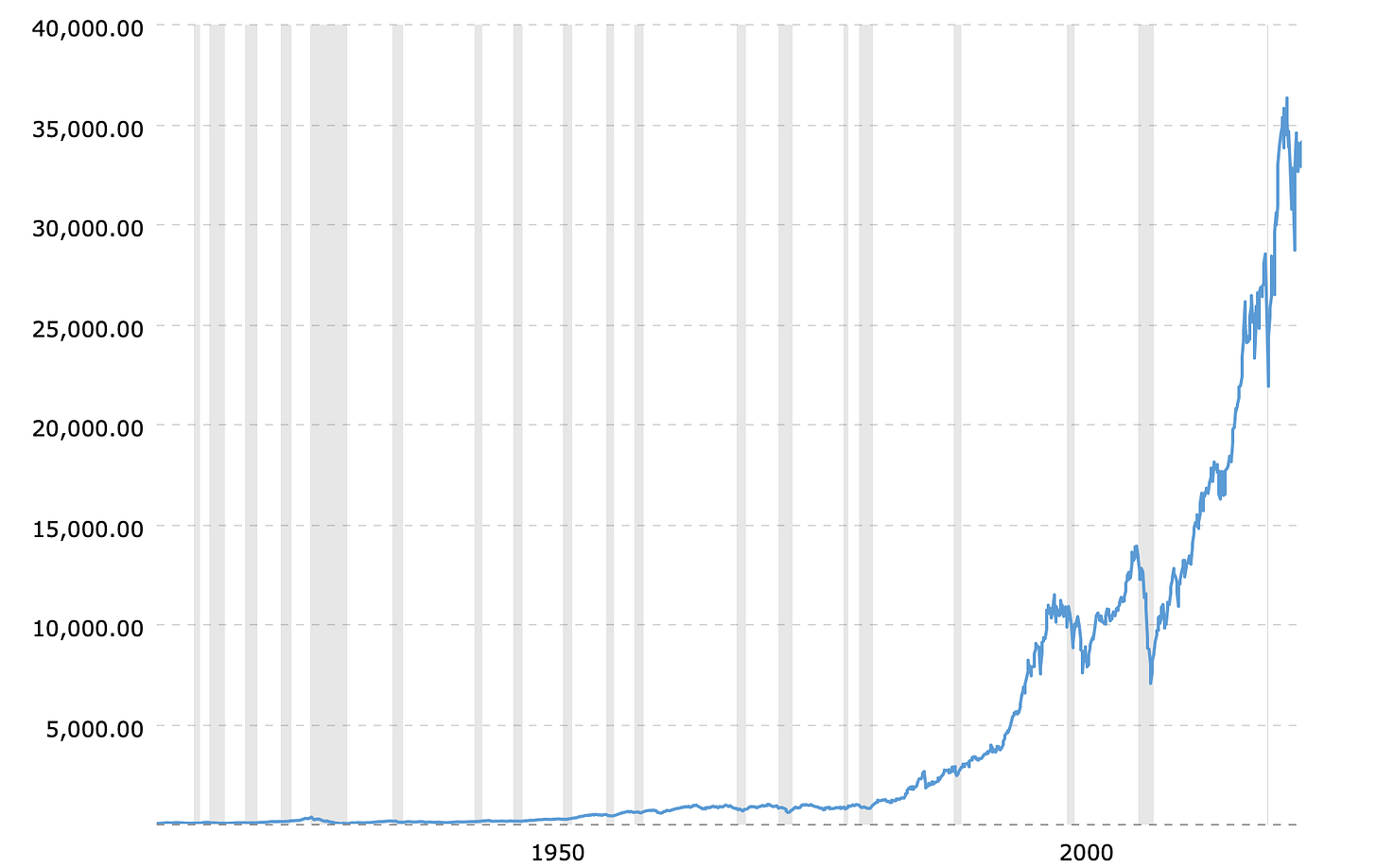

Stock indices were invented by journalists looking for a way to report on the performance and health of financial markets. The Dow Jones Railroad Average was the first stock index. It was created in 1884 by Charles Dow who published the Customer’s Afternoon Letter (now the Wall Street Journal). Dow started the more famous Dow Jones Industrial Average in 1896 to track the broader booming American industrial sector. Similarly, Poor’s Publishing established a 90-stock index in 1926 that later expanded to 500 stocks in 1957 — the S&P 500.

Then Vanguard changed the use case for indices in 1976 when it created the first mutual fund to track the S&P 500. Now the indices don’t just track markets. They are the market. S&P 500 funds have over $1 trillion in AUM.

It’s hard to imagine anything ever unseating the S&P or the Dow because they own both mindshare as market benchmarks and massive dollar share as “passive” funds.

While nothing is likely to unseat the major indices, new indices form all the time. There are now more indices than stocks.

Why do we need so many indices? One reason is that it gives investors better benchmarks for managers with specific strategies or mandates. By the same mechanism, more indices give managers better tools to think about relative hurdles for investments they consider. If a manager doesn’t think a prospective investment can outperform a relevant targeted index, he shouldn’t make it because that capital would be better off in the index.

AI is the major theme of the market today and maybe the defining technology for the next several decades. A lot of capital is being allocated to AI in both public and private markets, yet we don’t seem to have great indices to track AI performance. If AI is to be as big as we think it will be, we need well-crafted indices to track the sector’s financial performance, give us a sense for how expensive the space is, and benchmark AI-focused investments against.

I’m using two indices I created to answer these questions: the AI Average Index (AIAI) and the AI Hardware Index (AIHI). You can track them on Google Sheets here.

Indices to Benchmark AI Performance

The AIAI and AIHI follow similar methodologies as the S&P 500 — there are some guidelines, but I have discretion over the representation of how the indices populate. Both indices aim to track a set of tech companies developing key pieces of AI hardware and/or software with infrequent changes to the constituents.

These are the guidelines and make up of each.

The AI Average Index (AIAI)

The AIAI consists of 30 blue chip AI companies listed on US exchanges with a market cap over $5 billion. The company’s core product offering must also involve at least one of the following:

AI compute or networking e.g., GPUs, chip fabrication, cloud services, switches, etc.

Generative AI or a large language model for chat

Some proprietary AI model or deployment

AI-focused data management tools and services

Self-driving or other machine automation technology

The AIAI is equal weighted across the selection set and rebalanced quarterly. Changes to the selection set can be made at any time if/when constituents no longer meet the above criteria.

The 30 companies in the AI Average are:

The AI Hardware Index (AIHI)

The AIAI consists of 25 AI hardware companies listed on US exchanges with a market cap over $2 billion. The company’s core product offering must also involve at least one of the following:

AI chip design or fabrication

Memory production

Networking hardware

Vision or sensing hardware

Other AI-related hardware or hardware services such as equipment, server production, or chip testing

The AIAI is equal weighted across the selection set and rebalanced quarterly. Changes to the selection set can be made at any time if/when constituents no longer meet the above criteria.

The 25 companies in the AI Average are:

A note on the 30-stock and 25-stock sizes of the indices. Some critique the Dow’s 30 stock makeup as an ineffective representation of the overall market vs the S&P 500, but a limited set of stocks makes sense for AI indices where we should assume concentration amongst winners. It’s unlikely that there are 500 publicly traded big winners focused on creating AI products and services even if most of the world uses AI as they do the Internet.

Is AI Too Expensive?

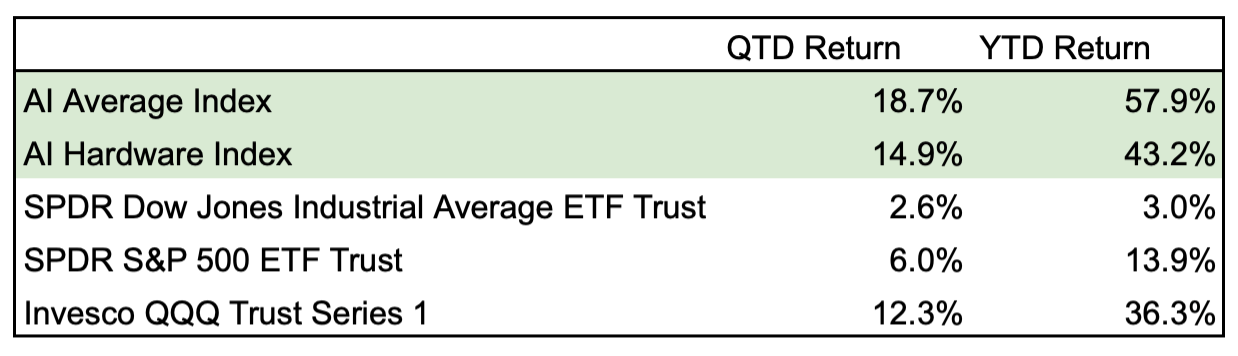

If you follow markets, you know AI has been the story of the year. It should come as no surprise that the AIAI and AIHI have performed well:

Even beyond AI’s relative performance vs the indices, individual AI stock performance has been fantastic. The average stock in the AIAI is up 61.3% YTD, while the average stock in the AIHI is up 56% YTD. NVDA, in both the AIAI and AIHI, is the consensus AI winner, up over 175% YTD. TSLA and AMD are also both up over 100% YTD and in both indices. PLTR, META, and MDB are all up 100% YTD in the AIAI, while SMCI is up over 200% in the AIHI.

With NVDA trading at over 20x NTM revenue and 47x NTM EPS, the obvious question is are we in an AI bubble?

The averages would say perhaps not. At least not like 2021.

The AI Average trades at 9.8x NTM revenue vs its five-year high of 15.1x and low of 6.2x. The AIAI trades at 60.5x NTM EPS vs the S&P 500 at 18.7x, while consensus estimates forecast 36% EPS growth for the AIAI in 2024 vs 11.7% for the S&P. So, as unscientifically as I can make it, the AIAI is expected to grow earnings 3x and trades at roughly 3x the EPS multiple.

The AIHI trades at 7.4x NTM revenue vs the five-year high of 8.2x and low of 3.7x. The AIHI trades at 36.7x NTM EPS vs the S&P 500 at 18.7x, while consensus estimates forecast 33.5% EPS growth for the AIHI in 2024 vs 11.7% for the S&P. Thus, the AIHI trades at at a 2x premium earnings multiple premium to the S&P with 3x the earnings growth.

Mean Mean Reversion

Edward Chancellor relayed a fantastic quote in The Price of Time (recommended reading):

“The great stock market bull seeks to condense the future into a few days, to discount the long march of history, and capture the present value of all the future.”

— James Buchan

The outperformance of both AI indices relative to other markets is exciting, but we should be wary of how much of the future AI bulls are condensing into a few days.

Meaningful AI revenue for many of these companies is further away than stock prices seem to discount. The infrastructure build is real and tangible, but saleable software products are early. Many companies I speak to expect significant AI revenue over time but not in the next 12-24 months.

Euphoria, as it always does, convinces believers and skeptics alike that they’re missing out. The result is increasingly less price sensitive marginal buyers who fuel higher prices. But calling a bubble too early only to watch it explode upward can be just as painful as riding one down after it bursts.

Regardless of what happens with AI stocks in the near term, I bet the AIAI outperforms the DJIA over the next decade. AI will provide an investment ground as fertile as the Internet did, perhaps even more so. If you have the aptitude to hold through volatile stock prices, the indices of the future may offer returns better than the indices of the past.

Great article; thanks for sharing your index construction methodology. I only wish you’d taken the opportunity to say how poor an index the DJIA, based on simple stock prices. While it does have high top-of-mind awareness, investors would be better off if it were no longer cited so often in publications and on business television.