Be Careful What You Wish For

How to think about investments like a bettor

“We don’t bet. We invest.”

I’ve seen and heard many asset managers make that claim, and it always rubs me the wrong way. One of my partners once insisted that we only use the word “invest” at Loup to my strong resistance. You probably know by now that I’m a free speech proponent. We say bet at Loup.

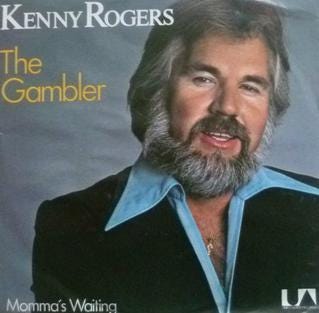

To bet is to risk a sum of money on the outcome of a future event. An equity investment is a bet that the prospects of a business are brighter than the current stock price demands. Good investors, like good gamblers, bet when the odds are in their favor, not just because they think something is going to happen.

To be a good investor, one must be good at understanding the odds. Here’s where things get tricky. Our understanding of the odds is influenced by our biases both before and after the bet.

We go into every bet with predisposed ideas that may or may not be relevant to processing the odds at hand. When we make a bet, often in accordance with our predispositions, those existing biases are strengthened to further distort our ability to price the ongoing odds of our wager. Every bet comes with a wish for a favorable outcome.

We need to be careful what we wish for in placing our bets. There are two ways to achieve that:

1. Acknowledge our biases

2. Use numbers to understand your wishes

Acknowledging Bias

Inflation has turned everyone into Fed policy experts as we contemplate what will happen to the market. All of that “expertise” comes with heavy bias.

Let’s oversimplify the outcomes of inflation x Fed policy into two categories:

Inflation is persistent, the Fed is behind the ball, and it’s going to be more painful than people realize. Rates need to be much higher than they are now to affect inflation, and we’re headed toward recession. We’re headed for a bear market.

Inflation is transitory, and the Fed will engineer a soft landing through modest rate raises. The market is going to be better than people think.

You’re predisposed to believe in greater odds of one case or the other before you even start processing the evidence. You likely fall in the persistent/bear camp if:

You’re a Republican

You follow the Austrian school of economics

You believe in crypto

You hold a bunch of cash

You’re adept at shorting

You tend to be bearish or skeptical in general

You likely fall in the transitory and not too bad camp if:

You’re a Democrat

You believe in modern monetary theory

You believe the government should engage in broader social spending packages

You’re fully invested with minimal cash

You’re down big in the market

You can’t hedge or short

You tend to be bullish or optimistic in general

These are obvious generalizations, but I’ve found them to be accurate. I fall into the first camp for all the listed reasons other than being politically independent. Because I recognize where I fall, I spend most of my time trying to prove the idea of persistent inflation and an inevitable bear market wrong.

Will inflation get better? Probably with easier comps later this year, although hard to say if we’re going to enter a wage/price cycle. What if the Fed doesn’t actually have to raise six times this year? They probably won’t, no matter how far behind the ball I think they are. What if the balance sheet reduction isn’t as harmful to equities as I think? Haven’t been able to prove this wrong yet. What if the Fed can engineer a soft landing and avoid recession? Historically, the base odds don’t favor this outcome, but it’s possible.

It will be rare that you decide your instinct is wrong, but continuous testing of your predispositions is the only path to independent thought. Proving yourself wrong is the most contrarian act of all.

Understand What’s Priced In

The price of an asset helps the bettor understand two things:

What must happen for the bet to pay off. In the case of an equity investment, price roughly defines how much future cash flow the business must generate to justify the investment given some discount rate.

Given a necessary outcome, the bettor can assess the odds of that outcome.

We’ve gone through the example of Tesla here before. The price demands an incredible future to be an acceptable investment. It demands an even more incredible future to be a great investment. I think the odds of the latter case aren’t very favorable. Tesla believers disagree. That’s how markets are made, and the market will ultimately decide the truth.

The point isn’t to rehash the tired debate of Tesla’s future, it’s to illustrate how an investor should think like a bettor to turn price into outcome, then assess the odds of such an outcome.

One of the greatest misperceptions about investing is that it’s only about being right. If you only try to be right regardless of the odds, your long-term returns are bound to be disappointing. It’s like betting moneyline on the favorite to win every football game. You might get most of the games right, but you’re not going to make much money. You’ll probably lose money with that strategy, same as in the stock market. We’re seeing that now as sanity returns to some of the highest-flying tech and growth names. When you hear “sanity returns” in the market, that’s code for bettors reassessing odds in a more rational way.

Good investing requires betting heavily when the odds are in your favor as defined by the price. If you bet on great companies when the odds are in your favor, you skew the likelihood of positive investment performance in your favor by maximizing upside and minimizing downside.

Use price to understand what must happen, determine the odds of that outcome while understanding your biases from the prior step, then bet.

Agree with Larry, and thanks for the note about the book. Adding:

In addition to our own biases of "confirmation", "recency", "identity", etc., public markets express collective biases. The excess swings up or down illustrate this. And currently we have naive followers making bets based on a tweet or a text message from a friend. These gamblers will push stocks higher late in the cycle and likewise push assets down late in the cycle.

Another book on Doug's theme, "The 5 Mistakes Every Investor Makes," by Peter Mallouk.

Doug - I think this is your best posting yet. "Proving yourself wrong is the ultimate contrarian bet" - in a world where changing your mind is seen as weak, acknowledging there are multiple potential outcomes is confused and the phrase "I don't know" has been deleted from from discourse - you hit the nail on the head - if you have never read the book Sway, The irresistible Pull of Irrational Behavior by the Brafman brothers - which hilariously explores how unconscious bias impacts decision making - I will send to your office. Maybe I should start a substack called "The Unconscious Profit" :)